Researchers discover a coral superhighway in the Indian Ocean

Despite being scattered across more than a million square kilometres, new research has revealed that remote coral reefs across the Seychelles are closely related. Using genetic analyses and oceanographic modelling, researchers at Oxford University demonstrated for the first time that a network of ocean currents scatter significant numbers of larvae between these distant islands, acting as a ‘coral superhighway.’ These results have been published today in Nature Scientific Reports.

This study couldn’t come at a more timely moment. The world is once again watching, as El Niño devastates coral reefs throughout the Indian Ocean. Now we know which reefs will be crucial to coral recovery, but we can’t pause in our commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and stopping climate change.

Senior author of the study, Professor Lindsay Turnbull (Department of Biology, University of Oxford)

Dr April Burt (Department of Biology, University of Oxford, and Seychelles Islands Foundation), lead author of the study, said: ‘This discovery is very important because a key factor in coral reef recovery is larval supply. Although corals have declined alarmingly across the world due to climate change and a number of other factors, actions can be taken at local and national scale to improve reef health and resilience. These actions can be more effective when we better understand the connectivity between coral reefs by, for instance, prioritising conservation efforts around coral reefs that act as major larval sources to support regional reef resilience.’

The researchers collaborated with a wide range of coral reef management organisations and the Seychelles government to collect coral samples from 19 different reef sites. A comprehensive genetic analysis revealed recent gene flow between all sample sites - possibly within just a few generations - suggesting that coral larvae may be frequently transferred between different populations. The results also hinted at the existence of a new cryptic species of the common bouldering coral, Porites lutea.

The genetic analyses were then coupled with oceanographic modelling, simulating the process of larval dispersal. These simulations allowed researchers to visualise the pathways coral larvae take to travel between reefs across the wider region, and determine the relative importance of physical larval dispersal versus other biological processes in setting coral connectivity.

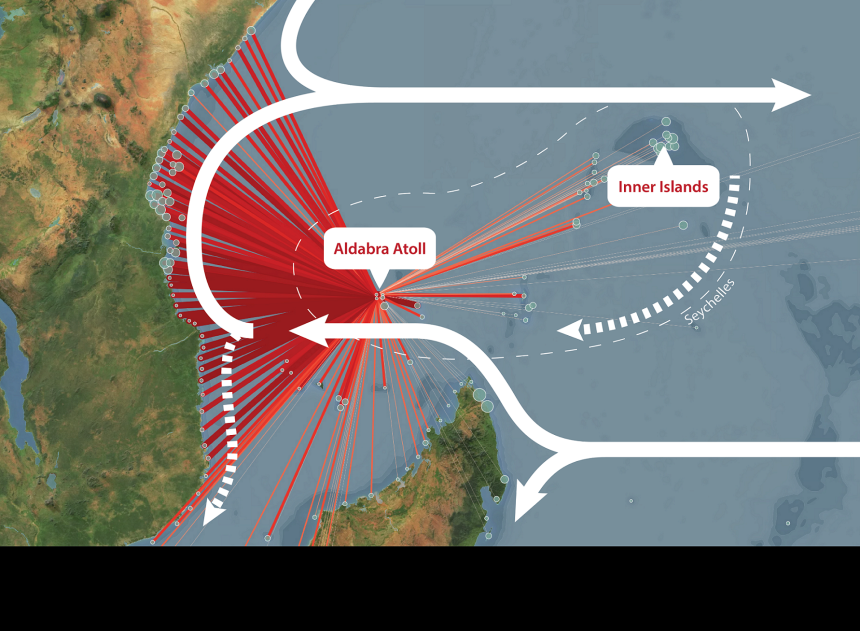

This revealed that dispersal of coral larvae directly between reefs across the Seychelles is highly plausible. For example, coral larvae spawned at the remote Aldabra atoll could disperse westwards towards the east coast of Africa via the East African Coastal Current. From here, they would then travel north along the coast, with some potentially even reaching the South Equatorial Counter Current, which could bring them eastwards again back towards the Inner Islands of Seychelles.

Map of the southwest Indian Ocean, with red lines connecting Aldabra Atoll, Seychelles, to simulated downstream coral larval destinations, primarily in East Africa. Solid white arrows show major current systems, dotted white arrows show minor or transient currents. The new study suggests that strong connectivity within Seychelles is established clockwise, potentially traveling between the Inner Islands and remote Aldabra Group via reefs in East Africa, and centrally located reefs within Seychelles. Credit: Dr Noam Vogt-Vincent.

Map of the southwest Indian Ocean, with red lines connecting Aldabra Atoll, Seychelles, to simulated downstream coral larval destinations, primarily in East Africa. Solid white arrows show major current systems, dotted white arrows show minor or transient currents. The new study suggests that strong connectivity within Seychelles is established clockwise, potentially traveling between the Inner Islands and remote Aldabra Group via reefs in East Africa, and centrally located reefs within Seychelles. Credit: Dr Noam Vogt-Vincent.While these long-distance dispersal events are possible, it is likely that much of the connectivity between remote islands across the Seychelles may be established through ‘stepping-stone’ dispersal. This suggests that centrally located coral reefs in Seychelles, and possibly East Africa, may play an important role in linking the most remote islands.

Aldabra atoll, the largest coral reef system in the Seychelles. Credit: Christophe Mason-Parker.

Aldabra atoll, the largest coral reef system in the Seychelles. Credit: Christophe Mason-Parker.

The modelling data can be visualised in a new app: with just one click you can see how coral larvae from Seychelles potentially reach reefs across the whole region. The researchers suggest that this data could help identify major larval sources to be prioritised for inclusion in marine protected areas or active reef restoration efforts.

Dr Joanna Smith and Helena Sims (The Nature Conservancy) who support the Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan Initiative said: ‘The WIO coral connectivity study, by illustrating the connectivity of reefs within a network, can be used at national and regional scales in the Western Indian Ocean for Marine Protected Area design and management, as well as directing restoration activities. We look forward to using the results and Coral Connectivity app to inform implementation of the Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan.’

The study ‘Integration of population genetics with oceanographic models reveals strong connectivity among coral reefs across Seychelles’ has been published in Nature Scientific Reports.

Landmark study definitively shows that conservation actions are effective at halting and reversing biodiversity loss

Landmark study definitively shows that conservation actions are effective at halting and reversing biodiversity loss

Researchers find oldest undisputed evidence of Earth’s magnetic field

Researchers find oldest undisputed evidence of Earth’s magnetic field

Honorary degree recipients for 2024 announced

Honorary degree recipients for 2024 announced

Vice-Chancellor's innovative cross-curricular programme celebrated

Vice-Chancellor's innovative cross-curricular programme celebrated

New database sheds light on violence in Greek detention facilities

New database sheds light on violence in Greek detention facilities

New study finds plastic pollution to be almost ubiquitous across coral reefs, mostly from fishing activities

New study finds plastic pollution to be almost ubiquitous across coral reefs, mostly from fishing activities

Entering the 'twilight zone': could distant coral reefs provide a refuge for threatened aquatic species?

Entering the 'twilight zone': could distant coral reefs provide a refuge for threatened aquatic species?  Can remote sensing help us to protect coral reefs?

Can remote sensing help us to protect coral reefs?